October 11, 2009

Passing Strange (The Musical / Film)

A movie by Spike Lee documenting Passing Strange, a Broadway musical with lyrics and book by Stew and music and orchestrations by Stew and Heidi Rodewald.

Before my brief comments on this concert/play/movie, here’s the synopsis from wiki:

“A young black musician travels on a picaresque journey to rebel against his mother and his upbringing in a church-going, middle-class, late 1970s South Central Los Angeles neighborhood in order to find "the real". He finds new experiences in promiscuous Amsterdam, with its easy access to drugs and sex, and in artistic, chaotic, political Berlin, where he struggles with ethics and integrity when he misrepresents his background as (ghetto) poor to get ahead. Along with his "passing" from place to place and from lover to lover, the young musician moves through a number of musical styles from a background of gospel to punk, and then blues, jazz, and rock. He finally returns home.”

This is a fab film that really loves the theatre it archives forever. I laughed a lot and was just wowed by so much of the writing. I was also impressed by the staging of drugs, anti-capitalist politics and performance art, that even when sarcastic and demeaning (typical framing in mainstream or big budget contexts), was also playfully right on and potentially subversive. The many references to Passing were super bright, insightful, playful, and satisfying. Energetically, the film suggests a performance that really moved its audience. Lee’s gorgeous close-ups provoke visceral and emotional response. The dramaturgy of energy, of rising and calming vibrant presences, might actually be the strongest element in this production.

I'm kinda surprised that Passing Strange was never on my radar - not that I ever track Broadway (or even Berkeley Rep where it was developed) but I usually know about performances of any kind that are so full of issues I care about. But maybe because the project itself passes strangely. It passes as different or experimental with regards to Broadway but then seems to recuperate Broadway’s ideological standards of promoting universals and (white) social norms. I say passes strangely because it is never quite what it says it is. It’s complicated. Which might be related to saying, it’s a Black middle-class thing, a performance of multiplicity, paradox and shifting position.

When the writing is not sharp and wonderful, it's too cliché and dumbed-down. Stew, the writer/narrator/star, knows all the reasons not to reproduce a sucky Broadway show and then he tries to do it. I mean sure it’s a personal narrative and maybe it’s even a True Story. But does a play smart enough to acknowledge feminism have to make every shift in a boy’s life be dependent on mom or girlfriend?

Did the writers and producers think that the only way to stage a non-Broadway song on Broadway is by quotation? The influences of punk, funk, minimalism, and performance art have been integrated into mass media and Broadway performance for years. In Passing Strange, the default is show tune ballad. Only when part of a play within play, the punks in Berlin for example, can we experience ‘alternative’ musical stylings. This default setting wouldn’t bother me so much if it was just aesthetic, but it is also ideological. Not just one drug scene, but pot, acid and speed are all instrumental to his artistic/political formation. But shit, is all the countercultural experimentation simply a distraction from the reals (ideals?) of family, christmas, and musical theatre? This default to normative family somehow can’t recognize that the ways we construct family are central to the lead character’s struggles with identity and authenticity, with finding what’s real. What's next - a thanksgiving musical where a gaggle of freaks gather to un-ironically feast on turkey with a 'medicine day' chaser? (Sorry if that reference is opaque. There are 100 people who know exactly what I’m talking about.) Anyway, help me out as I stumble in this slippage between hi and low, downtown and midtown, rich and poor theatre. I feel duped.

PS.

I would like, at least once in my life to have one of my own performances documented so well.

PPS.

Duped means deceived and the word originates form 17th cent dialect French about some bird whose appearance was supposedly stupid.

September 16, 2009

WHY I READ MY TEXTS IN PERFORMANCE

WHY I READ MY TEXTS IN PERFORMANCE:

THE ROLE, MEANINGS, AND PRESENCE OF THE TEXT

1. Because they’re fresh, reworked until the last minute, just written and I don’t have time to memorize while dealing with production, promotion, choreography, costumes, lights, volunteers, ticket sales, press, documentation, props and rigging, shopping for necessary stuff, and practicing the action, the dancing, and/or some crazy stunt.

2. Because I saw Karen Finley read, mixing trance ritual performance with alienated Brechtian interruptions... a schizoid presentation of emotional release and the commentary on the release, refusing to let herself, or the audience, get lost in the trance, provoking us, often with humor, to recognize the absurdity and artificialness of the theatre, of our relationship to the art and artist, and from there to recognize the absurdity of the violence or trauma that she is communicating. After seeing Karen Finley read in performance I not only gave myself permission to read text without memorizing but I gave myself permission to put my whole body-voice into performance. Within six weeks of being a chorus dancer in Finley’s performance* I was performing Saliva under a freeway in SOMA/downtown San Francisco. This was my birth as an artist. (*1988, Life on the Water, me dancing in Jennifer Monson’s line dances, naked for one dance and then in Finley’s personally chosen drag, getting to watch her five nights in a row.)

3. Because Jeanette Winterson wrote Written on the Body among a generation of feminist performers, writers, artists and thinkers that articulated the ways that language is inscribed on the body, the ways that culture and politics and society and history and tradition get written into our gestures and behavior, influencing all the texts and performances that we (co)produce in daily life.

4. Because Carolee Schneeman pulled a scroll from her pussy and suggested that the text comes from the body as well as from a cultural inscription upon the body (Interior Scroll, 1975). I have pulled text from my ass while hanging suspended above an audience, asking what would the ass – the other mouth, lips, orifice – say? (Highways, 1993, Rites of Ecstacy & Transformation, curated by Doug Sadownick). This led me to write a series of body texts about racism after the LA riots, poetically imagining what the white male queer body might say if it could bypass mind/media/society. Of course this was a utopian imagining, not a ‘realistic’ trip. I pulled texts from my ear, nose, mouth, and then had a naked male assistant come on stage, put on rubber gloves and pull a text ensconced in a condom in my butt. (Heat, Hennessy, 1993).

5. Because Guillermo Gomez Peña defended the practice for all the above reasons and more in his essay, “In Defense of Performance.” (LiP Magazine, 2004).

In drama theatre the actors are not usually also the authors. On the other hand, in performance art the performers are almost always the authors. In most theater practice based on text, once the script is finished, it gets memorized and obsessively rehearsed by the actors, and it will be performed almost identically every night. Not one performance art piece is ever the same In performance, whether text-based or not, the script is just a blueprint for action, a hypertext contemplating multiple contingencies and options, and it is never "finished." Every time I publish a script, I must warn the reader: "This is just one version of the text. Next week it will be different."

(Maybe a later or earlier version of the essay actually mentioned reading text..., k)

6. Sometimes I have the text in hand so that I can improvise in relation to it, using the text as the stable language and my body/voice/performance in live interaction with an audience as the instable, flexible, available for insight and response language. (Box, 1996 – speed reading cue cards with as many additional ‘fucks’ and other interventions as possible in a staged telephone conversation about prison and race in the US, the OJ trial, and more. Chosen, 2003 – riffing off cue cards that held the keys points for an analysis/deconstruction of the idea of being chosen – to live in Israel, to be an artist, to be queer. Heat, 1993, in the closing section I had several pages of text, all of the source writing, and would read only selections from it... different stuff in each performance... although the document was a living document with notations and circled text and moved towards a finished text (without ever arriving) as the work was repeatedly performed.

7. The text as book as fetish object, invested with repeated touch and performance energy (the symbiosis of audience and artist and ancestors)... hand-made books with images or painting (Saliva, 1988/9 and Palpitations, 1997). Text boards (Sacred Boy, 1990/92) with updated versions taped over previous, adding notes from the previous to the typed version of the 2nd and then beginning the process of notes again... Not unlike a favorite or family bible. An old manuscript. A palimpsest. Revealing the ritual of process: Where did this come from? I wrote it and printed it and glued/taped/bound it into a book.

8. In Sol niger I am working, after the alchemists, with language as a material to be transformed through play, study and manipulation.

Projected text – recalls CNN news bar (“The CNN news bar is a bar to news” Terrance McNally, Crucifixion 2005), and other sites of constantly streaming headlines, stock markets, and military-capitalist propaganda.

I want to speak and write in multiple layers, a polyvocal voice, multiple personality dis/order:

Exploring the ways that my language is not my own (and neither is yours)... through cultural inscription, adopting of certain ideological or political positions. Dancers know that the shapes you make influence feelings and thoughts, not only that you communicate, but that you feel or think.

Revealing a voice that has experienced relentless interference from excessive unnecessary information and promotion, including an obsessive repetition of brand names - commodity fetishism and corporate infiltration into daily life – and ‘spectacular’ news that, as Chomsky has articulated, manufacture consent.

Dancing the collaboration between analytical and emotional voices.

An attempt to poetically synthesize a large amount of focused reading, theory, & analysis, revealing the process of filtering language and ideas through my body/consciousness the way I process food... transforming it into energy or shit or...

A complicated/multiple voice includes found text and plagiarism (more like samples than thefts, almost all citations are credited). I am sparked by conversations and art. While at MacDowell Colony working on the Sol niger text I saw Dust a film by Eric Saks in which the word Islam was rhymed with lip balm. I was sparked. That’s the kind of interference I want. These two words opened a portal into a kind of language play that gave my writing a style I hadn’t used before... but that I’d been looking for (my own version of) since reading about Pollesch.

September 5, 2009

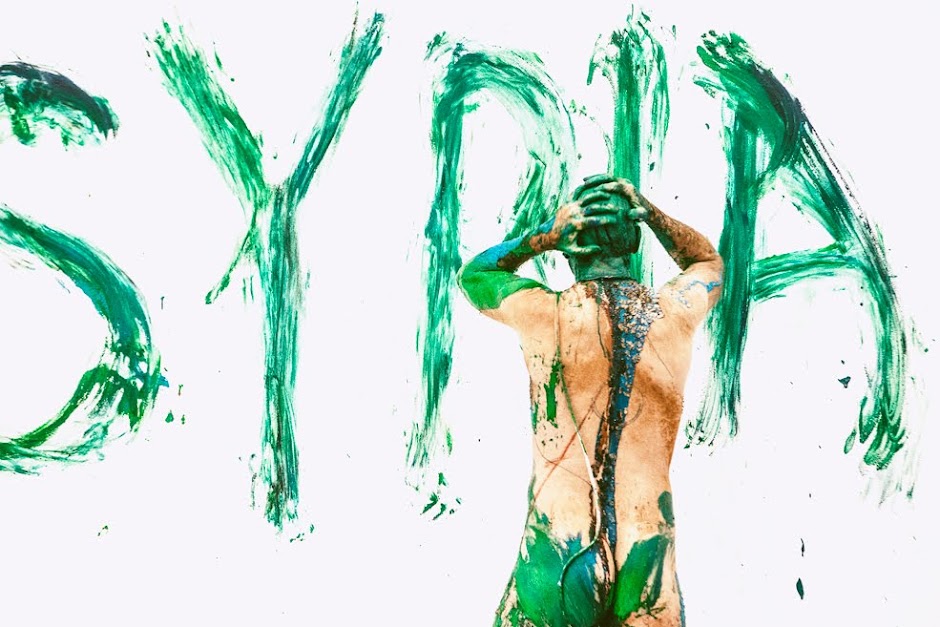

Photos from The Keith Score

PERFORM THE KEITH SCORE

Here's a story about performing improvisation followed by everything you (or I) need to perform my most recent 'piece'. Of course you can also read this as a description of recent improv performances...

Keith Score

A solo performance by Keith Hennessy developed unintentionally while improvising.

Written documentation, July 20, 2009, Berlin

I have been performing solo improvisations since the early 80s. I think my first spontaneous choreographies for an audience were in 1982 or 83 at The Alchemy Lab, a weekly improv ‘club’ held in a side room of the Fillmore West in San Francisco. Since these earliest experiments I have merged talking and dancing to extend postmodern dance into mongrel post-genre performance[1]. When I perform improvisation I am sharing a particular research practice that informs nearly every aspect of my life: how I make art, how I live in my body, how I participate in social movements, how I clean the house, how I relate to others, how I experience or sense the world around me, how I make decisions, how I make money, how and what I teach, how I sense and play with energy, how I relate to spiritual and religious ideas and feelings, how I consider memory and history. Although my influences are many and ongoing, here is a list of the primary artists and situations that have inspired me to improvise in performance: the wide network of contact improvisation jams and festivals, Dena Davida/Catpoto (Montréal), Lucas Hoving, Terry Sendgraff, Ed Mock, Sara Shelton Mann and Contraband, Mangrove, Akira Kasai, and the performances Unsafe, Unsuited (with Patrick Scully & Ishmael Houston-Jones) and Antibody.

In the past year I’ve performed a few solo improvisations that have generated a series of actions, images and moments that I would like to gather into a new choreographic project. I intend to perform this work and am also interested in it being performed by others. This work, tentatively titled Keith Score, is my first piece made without a political or ritual intention distinct from the ritual and politics of improvisation, i.e., distinct from performing the making of performing, i.e., my first unintentionally sourced choreography/performance. This score will most likely be updated after further testing in performance and/or watching videos of past performances.

Tech requirements.

Space

A space in which all of the audience can see the floor.

In the round is possible but other audience configurations are preferred, e.g., frontal, two or three sides, ¾.

White or grey floor preferred.

Present the space as raw as possible: no wings or back curtain or objects that can’t be removed.

Light

A fully lit space, prefer no color. Some light on the audience.

2 (two) instruments, on the floor, with long cables, to be manipulated/placed by the performer.

1 (one) light operator, available for spontaneous requests from the performer, based on pre-discussed options.

Sound

1 (one) microphone with cable. For extra safety, tape the mic to the cable.

1 mic stand.

On stage monitor if possible.

Reverb if possible.

1 (one) sound operator, available for spontaneous requests from the performer, based on pre-discussed options.

The sound/light operator can be the same person.

Costumes, Objects

Carried on stage in two cheap plastic shopping bags, preferably not identical.

• Digital camera.

• Black ruffle under shorts, like what a vintage cancan dancer might wear.

• Flesh-colored dance belt (cover genitals, reveal ass).

• For women with mid-large breasts, a flesh-colored bra.

These under-garments are not about modesty; they are about erasure, history, fetish and representation. They are intended as the most minimal costume that transforms a naked body into a ‘dancer’s body.’

• Long strand of pearls (fake or fresh water), to wrap 3 times around neck.

• Sequined gauntlets, approx. 5-8”. You’ll probably have to make your own.

• Stirrup tights. Preferably a little too big, bright colors, floral or of nostalgic or personal significance.

• A mask. My friend found my mask on the street. I will try to figure out what it is and buy more of them. Until then, the mask should be latex, cover the whole head, preferably not have a mouth hole, have some kind of hair, and be as unmonstrous as possible.

• A sequined dress. Preferably fabulous, or fabulous kitsch, not perfectly fitting, old/vintage, mid-thigh length.

Optional

Some object, costume, or food that you have never worked with. To use if you feel stuck, shitty, lost and have already (1) tried everything I’ve suggested or that you know to keep an improv alive, and (2) have reported to the audience that you are stuck, feeling shitty, and/or lost.

Time

The length of the piece is 30 to 70 minutes.

The Score

One

Walk out in some version of street wear, clothes you wear everyday, not special. Introduce yourself and say hello to the audience. Say a few more things.

I might introduce myself, or ask the audience if they’re comfortable and ready. I ask if someone is willing to document and I give them the camera. I tell them to pass it along if they get bored or uninterested in taking pictures. In the past I have told the audience what I’ve pre-decided and that the rest of the performance is some kind of open improvisation, often referencing certain tricks or devices I’ve been doing for years. I’ve been questioned about this device of performance informality, this performance of “I’m just another one of you.” Am I sincere or manipulative, casual or calculating? Yes; And. I try to act reassuring, inclusive, and yet prepare them for an adventure.

Two

Take off clothes (everything) and put on black ruffle shorts. Start to drool saliva into palms of hands and rub it into your legs, stroking down towards feet. If your legs are hairy, your goal is to smooth the hair. Before you run out of spit, or after 5 or 6 drools, tell the audience that you don’t have enough spit to complete the job, and suggest that they get ready to contribute. If someone snorts or jokes about coughing up phlegm, politely instruct them to gather only saliva, only from the mouth. Go towards the audience with cupped palms. Request volunteers. After 1 or 2 contributions, smear the saliva down your legs. Continue, working different sections of the audience, until you have covered all of your exposed legs from hem of shorts to ankles. If you have a particularly big contribution, press both palms together and then pull apart to show the audience, catching the light with the suspended saliva. When you feel done with this task, walk back to the stage or playing area, smearing any excess saliva into your head hair, torso, and/or face.

Three

Take off black shorts. Put on the dance belt (and bra). Say: “I am not wearing this costume to make me look good.”

Put on the pearls. As you wrap them three times, say: “Pearls mean mother.”

Put on gauntlets. Say, “Sequins mean gay.”

Put on mask.

Stand in parallel. Think Paxton’s stand, the small dance. Feel any tension in the body and play with exaggerating (tightening) and relaxing it. Turn head to get used to mask and how people respond to it.

Four

Shift from two-foot stand to balance on the outside of one foot for 2-3 minutes. This will involve a lot of falling off balance, adjustments, changing facing, waving of arms and free leg to maintain balance. When possible, drop arms and try to relax as much of the body as possible. This should be rehearsed! I’ve been standing (and turning, and jumping) on the sides of my feet for years and I still feel a little sore, overstretched in the ankle, the next day.

Five

Improvise dancing. Keep your energy bright. Don’t stay on your feet. Don’t stay facing the audience. Try going to a new place in the room to stand on one foot (flat or side).

Six

When you start to breath more deeply, heavily, play with sucking the mask to your mouth. Breathe audibly, rhythmically. Continue to improvise movement, space, action. Push yourself. If you can almost do the splits, play with stretching yourself. If splits are easy, try some other contortion. Look for body limits, borders, and play there. Follow sensations, respond to impulses, don’t get distracted with comedy and audience laughter. Continue to give yourself tasks, explorations, adventures. When in doubt, run to a new location and stand on one foot. Or hold your breath as long as possible, moving only on the exhale, or the inhale.

Seven

Use a finger to push the mask into your mouth. Biting from the inside changes the expression of the mask. Continue exploring movement.

Eight

Lift the mask part way off (half-way?) and turn it backwards, but leave it on your head. Continue moving, adding the game of twisting the body into shapes that play with perceptions of front and back. Headstands with mask face towards audience can be funny, curious, weird.

Nine

Go and get one of the floor lights. Bring it somewhere. Ask the operator to turn it on and dim all other lights. Add the second light. Focus it in some kind of counterpoint with the first. Take off the mask and leave it somewhere in the light.

Ten

Go and get the microphone. Stand somewhere in relation to the light/dark spaces you have just created. Swing microphone over your head. Listen. Adjusting length of cable, change the sound. Listen. Like a lasso artist or fire spinner, lower yourself to the ground until you are lying on your back. Fold one leg under you to recall the standing on one leg. Keep swinging the mic while remembering/translating the balancing on one foot. The audience will probably laugh with recognition and you might enjoy the absurdity. Stay focused on a most accurate translation, remembering.

The sound operator might choose to collaborate, changing the bass/treble or volume or speaker. His/her changes should be subtle, at least at first, so that initially the sound is coming only from the swinging mic and the dancer listening.

In Mexico I couldn’t have any floor lights so when I swung the mic in the fully lit space I walked closer to the audience and let some people be concerned that they or someone else might get hit, hurt. In Germany I began this section by measuring out the cable to make sure I didn’t hit pillars.

Eleven

Sit or stand, while still swinging the mic. Slowly decrease the length of cable until you can grab the mic. Speak slowly into the mic, listening and responding to the sound of your own voice, “A microphone is for speaking, or singing.” Say anything else, or make any other mouth sounds, that you want. Then say, at least once, “Now I will bake a cake.” Try to balance the mic vertically, on the floor, or on your body. Catch it as it falls. Repeat. Explore its movement and sound[2].

Twelve

Place the mic on the ground. Lay down with your mouth at the mic. Make a quick choice about where you want to be in the light. You can change location, or relation to light, or light positions at any time. Sing something, quietly. If you get distracted while singing, tell the audience what you’re thinking. This can lead to improvising with light, sound, mic, body, dance, language. You might tie the mic around your neck, or put it in your dance belt (or bra). You might drag it gently across the floor or around your body. (You also might do this much later…). In Chicago and San Francisco I focused more on making sound with the mic against my body or costume. In Mexico I didn’t speak as much because too many people didn’t speak English. In Germany I started singing House of the Rising Sun and then made lyric links to Summertime (thinking about descriptions of momma & daddy).

Thirteen

When you feel ready to change or if you feel lost or distracted, take off the pearls and sequined gauntlets. The next time you want or need to change (after 30 seconds or 10 minutes…), ask the tech operator to bring the lights back up. Move the floor lights and then put on a pair of stirrup tights, preferably floral, bright colored, or of personal significance. My stirrup tights were a gift from Remy Charlip[3]. You might tell the audience, briefly, the story of your tights while putting them on.

The performance is kinda free form by now. You might want to put on the tights and not change the lights. Or vice versa. Consider how much time you have and play it as best you can.

Explore moving in the tights. Be strict with your attention and clear with your intentions. Report (honestly or poetically) to the audience if you feel distracted, or are dropping one score or task to find another.

Fourteen A or B

Start to measure the space with your body. Go quickly, urgently, hungry for external guidance. As soon as you begin to indicate something, change, find something else to measure, match, indicate. Examples: Match arms, legs or torso to angles of walls, roof beams, audience seating. Match whole body length or angle to architecture, an audience expression, a mark on the floor or wall, follow the floor tape or an exit sign. Do this until you find something interesting to explore or repeat or a fresh impulse to follow.

Explore the space – the physical and social space. Climb something or get into the audience. In New York, I had asked for a light bar to be lowered towards the back of the stage. I used a square block to reach up and hang from it. In Germany I was lucky to be performing in a gorgeous converted barn with log beams (almost pillars) that I could climb between. Do something that expands y/our experience of the space. Stretch the idea of the theater, vertically or into the audience, or out a door or window, or even out of view of the audience. In Mexico, Germany, and New York my climbing was considered dangerous, even reckless by many (not all), in the audience. Calculate your risks and play within your range, stretching perceptual borders of ‘normal’ or ‘expected’ body, theater, dance, performance, space, time, presence.

Hopefully you can have a rehearsal in the space where you can see potential for climbing, testing the space. Asking permission in advance is more important in the US than in Europe and is more important in fancy theaters than in converted barns. I enjoy the space between provocation and building consensus. I like to include the presenters and the audience in the making, performing.

Fourteen A or B

Explore the space with sound. Talk, sing, sound as you wish. In Mexico I clapped my hands to test the resonance of the space and then I started singing (almost yelling) a loud tone. I played with changing my mouth shape to make a thick, polyphonic sound, filling the space and bouncing back into even more complex sound. The audience could really feel me, the room, themselves, the fusion of these. In New York (Dancespace, St Mark’s Church) I started growling louder and louder, pushing my voice and my relationship to the audience as far as I could, and in Chicago I sang a Christmas carol with equally intense broken (growling) tones. In Germany I didn’t do anything that tested the space sonically. Sometimes I’ll stomp my feet in loud, fast triplets.

Fourteen C

If you end up somewhere and want to reframe it with light, ask someone in the audience (or in a union space, ask a technician) to come on stage and re-position & re-focus the floor light(s). Sometimes a really magical ‘theatrical’ moment can be created. I love the tension/link between this magic and all the pomo, Brechtian, and anti-representational approach to performance and theater tech design.

Fifteen

Take off the tights and the dance belt (and anything else you might still be wearing: pearls, gauntlets, bra, optional items).

Put on sequined dress.

At this point you should have enough sensations in your body, awareness of breath, charged relationship with your environment – physical, energetic, audience, all – that you can just live, simply. Stand. Look. Fall down. Crawl. Walk. Talk. Sing. Dance. Don’t dance. Shake. Vibrate. Breathe. Roll.

Sixteen

You can always go back to mic, lights, reporting what you are doing or not doing, singing, exploring space, climbing, revisiting anything you’ve done before (including standing on one leg, testing limits of the body). If I notice that some spit has accumulated in my mouth, I tend to intentionally gather more and more, and then play with drooling, sucking, drooling onto the floor, or perhaps licking foot or hand or floor. Slowly drooling onto hand or floor, with spit illuminated by side or back light, is ‘magical’ even if also ‘gross.’ Spitting is of course optional. I’ve been playing/working with saliva – mine and others – since at least 1988 (Saliva). What have you been playing/working with?

Seventeen

You find or craft or decide the ending. You can decide by pre-determined length of time or by spontaneous decision. You can work with a cue from the light operator, or from a visible timepiece. In Mexico I wore a watch and ended at 31 minutes. I New York I said I’d go 45-50 minutes but I went 75. You don’t have to end in the dress. You can really follow or drive this performance to the conclusion you want.

[1] Mongrel: term adapted from Gulko, artistic director of Cahin-caha who uses the French word bâtard interchangeably with mongrel to describe his performance work. My mongrel is a bastard pup of dance, contact improvisation, circus, experimental theater, visual & conceptual art, theater design, lecture, performance & body art, site-specific art, stand up, Judson, Ridiculous, vaudeville, dance-theatre, music and sound art, public and activist art, object theater and more.

[2] Two references from a filmed interview with Simone Forti at Bennington.

I will bake a cake, as a dada-ish description for making a dance or happening. Balance an object and watch it fall, as a way to make a score for dancing.

[3] Remy Charlip – choreographer, children’s book author, healer. Charlip performed in early works of The Living Theater, was an original company member and costume designer with Merce Cunningham Dance Company, is the inventor of Air Mail Dances, the author and illustrator of numerous whimsical provocations for children, and has been deeply engaged in avant-garde dance, art, performance and somatics since the 1950s. He has lived in San Francisco for nearly 20 years. I relate to Charlip as my gay art uncle.

QUEER! a workshop

Satu Herrala, one of the participants wrote about the class for Corpus a cool site that you can check out here.

http://www.corpusweb.net/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1263&Itemid=35

I didn't have a particular pedagogy for the class but each day I worked with an idea or a particular theorist and tried to come up with improvisation and composition exercise to explore that idea, e.g., Gloria Anzaldúa on borderlands, Trinh, T. Minh-ha on movement between margins and centers, Kate Bornstein's work on analyzing one's personal gender(s)...

Just to have that many queer-identified and queer-curious people in one dance class was excellent.

Here's the final paragraph of Satu's report:

On the last day, we were looking at each other for a long time. People suddenly had so many faces without trying to fix one. As we returned to language after this simple but powerful experience, we talked about binary thinking and how to undo those patterns of oppositions. To undo the thinking, we have to undo the language - female and queer are oppressed not only socially and politically but also in terms of signifying meaning. Keith quoted Trinh T. Minh-ha who said that: “Meaning has to retain its complexities - otherwise it will just be a pawn in the game of power.” Her writing, together with many other feminist writers, operates between theory and poetry. That borderland is a place where new meaning can occur. Our borderland is the body. If we want to challenge the norms and representations of sex, gender and race, dance and performance is a good place to be.

July 5, 2009

Prisma Forum, Oaxaca & DF, Mexico

I wrote this while in Mexico City for week 2 of Prisma Forum a hybrid event that resembles a European contemporary dance festival (with all its hybridities of performance, choreography, laboratory, conference) with more participatory, communal and DIY aspects of popular social forums. Instigated by participant interests, daily plenary sessions are complimented by several seminars, round tables, and informal discussions. At least 10 daily classes or ongoing workshops, from physical techniques in somatics, dance, yoga, and chi gung, to choreography and performance making influenced by a wide range of strategies from shamanism to permaculture, discursive questioning and experiential anatomy. In the late afternoon and evening there are several performances each day. Contemporary work from emerging and experienced artists from New York, many European countries, Mexico, Brazil, Israel, South Africa, Korea and beyond. A big vision and an extraordinarily generous commitment by the small team of Mexican organizers stewards this pioneering experiment.

The highlight of the first week (held in the city & small pueblos of Oaxaca) was a brilliant talk by Amaranta Gomez, a Muxe political candidate running for federal office. To a North American queer, muxe seems synonymous with transwoman, but Amaranta was quick to request that she not be called trans. Indigenous to the Zapotecas, muxes have a traditional social role. The word muxe, adapted from the Spanish mujer, identifies males who live as women. Muxes are pre-colonial, pre-Spanish. When I asked Amaranta if she worked in solidarity with LGBT activists, she briefly spoke of common struggles with AIDS and homophobia and that she was a member of ILGA, the international lesbian/gay NGO. However, Gomez said that muxes had more in common and more solidarity work to do with feminists than with those focused on queer issues. Amaranta spoke simply, directly, warmly and with a sharp wit, addressing more intersections of issues than any pomo interdisciplinarian could imagine addressing within a single hour. She embodied and shared generously her contemporary indigenous wisdom. Her talk became an inspirational reference for many of us, and we quoted her throughout the week.

I taught a 3-day workshop called Potential Shamanic Action. Staging the class as an encounter between a European-based international community of dancers with local Oaxaqueño artists of all ages, I framed a few simple ideas (the earth is sacred, everything is connected, the border is a space not a line) for experiential explorations in ritual and performance. Over 50 people participated, of whom half were Mexicans. We're still buzzing...

I hope to write more about this amazing and complicated encuentro but I'm still travelling...

June 4, 2009

Scott Wells & Dancers, Men Want To Dance

What Men Want

What Men WantScott Wells & Dancers

May 31, 2009

Part of the 2009 SF International Arts Festival

CounterPULSE, SF

Scott Wells makes wonderful dances for men and women and sometimes he makes wonderful dances for men. Wells treats modern dance like a sport in a postmodern fusion of relaxed lyrical dancing, physical comedy, and surprisingly tender partner acrobatics. The leaps, catches, cat like landings and spiraling falls to the floor reveal the company’s roots in the dance known as contact improvisation. What Men Want was a suite of four premieres, including two big works for an ensemble of eight men. In this meandering writing, I don’t review each piece. I’m exploring a few ideas, mostly about men dancing.

Wells’ work for men charms with a playful engagement of masculine clichés, anxieties and interventions. The work is so unabashedly straight, as in heterosexual, that it’s almost queer. I mean that Wells and his guys, regardless of their personal identities and affections, come across as straight dudes whose physical intimacy most often recalls the homosociality (aka male bonding) of a compulsively hetero locker room. At other moments of sensitive dancing and careful touch the choreography dares to intervene on hetero norms. We don’t expect sporty dudes to roll together quite so slowly. It’s queer in it’s intentional questioning of masculine performance. If there’s a weakness to this expansive view of hetero masculinity it’s the way that Wells’ choreography responds to nearly every gentle moment with a kind of defensive reaction of physical comedy, martial arts jokes, or just vigorous muscular activity. The choreographic rhythm is like a pendulum that inscribes a binary code, swinging from masculine to feminine, gentle to vigorous, sensitive to hilarious. This binary insistence is decidedly not-queer. The only device I contest is the ubiquitous ‘gay joke.’ There are a million variations - in dance, television, sports, Hollywood, advertising – in which two or more guys suddenly become aware of how intimate they’ve become, and the energy shifts, and the audience laughs. And that laugh, for queer boys, is too often a cruel laugh.

K. Ruby was a dance student and choreographer at Berkeley High 30 years ago. Recently, she told Linda Carr, the current head of Berkeley High’s dance program, how times had changed. With the addition of hiphop to the dance curriculum, it seemed to Ruby that more boys were dancing. She recalled that classes in the late 70s were predominantly female except for the occasional gay or soon-to-be-gay male. Carr pointed out that, sadly, today’s gender demographics were consistent with Ruby’s experience. And that’s the news in a town noted for its liberal and radical social politics, in a Bay Area known worldwide as a place for queer challenges to normative behavior. How much does gay anxiety and homophobia influence our dance cultures? Why is it so unusual for men to dance together in this culture we might call contemporary or post-European or even post-colonial? In Ballet, Modern dance, and the styles that follow, females are probably 80% of the practitioners, many in training since the age of four or five. Males start dancing later, take fewer classes, have significantly less competition for professional opportunities and consistently get more attention and resources. Despite the male dance superstars from Nijinsky to the Nicholas brothers, from Gene Kelly to Baryshnikov, and from Jose Limon to Savion Glover, dance – in the American popular imagination - continues to be gendered female, or feminine. Try to consider this while simultaneously and paradoxically noting that the most viewed YouTube video (100 million + hits) is a comic dance by Jud Laipley called The Evolution of Dance, AND the top prize for the past two years of Britain’s Got Talent was won by male dancers, who received millions of votes and even more YouTube hits. Diversity, a multi-racial, age diverse, all-male dance company, won this year’s prize and the 2008 winner was a 14 year old named George Sampson who performed a hiphop remix of Kelly’s Singing in the Rain. European and American boys and men are dancing but they’re still not taking modern dance classes in any great numbers. Scott Wells & Dancers operates within this larger social context of homophobic masculinity, gendered dance expectations, and special attention for dancing boys.

The two jewels of this oddly named evening of dancing were the smaller more formal works, Catch, a duet for two dancing jugglers, and Bach solo trio, danced by a solo woman and a trio of guys. I think I like Catch because of the lack of comedy. The duet connection between Aaron Jessup and Zack Bernstein (of Capacitor) was super sweet. All dance duets are about love, but some are less romantic than others. In this pas de deux with objects, the love was a shared loved. If I could call it Whitmanesque and not evoke sex, I’d call it the (chaste) love of comrades. They danced on and around each other’s bodies, always a red ball in hand, or traveling between them. As the work progressed, virtuosic ball tossing alternated with swirling lifts and spiral rolls over backs. Sometimes there was one red ball between them, but towards the end they each juggled five balls simultaneously, beginning and ending in perfect synch. Impressive. The dance ended the way it began, roles reversed, one man a landscape of body lying in a circle of light and the other walking the perimeter.

Bach solo trio opened with a short solo by Rosemary Hannon. Hannon (recently seen dancing with Non Fiction at The Garage) repeated a short phrase focused on the arms and torso. Hannon is tall, lean and articulate, a hyper-aware dancer whose long arms unfold in delicious detail to the ends of her fingers. Dancing in silence, her breath had a resonant presence. As she exited, the Bach began, and the men, Andrew Ward, Sebastian Grubb, and Cameron Growden, entered. As they repeated the same phrase as Hannon, I looked for difference and tried to determine which details were because of gender and which were due to the particularities of these bodies. The men were each and all more compact and dense than Hannon. They didn’t have the openness of shoulder flexibility nor the articulate detail in their fingers. Unlike Hannon, they hadn’t been taking dance class since early childhood. The openness and breath in their chests felt like a distant reminder of Hannon. The men really came to life in the curvy tumbling and floating handstands. There was a section of low spinning into and up from the ground, weight on and off of hands, that recalled the Brazilian dance/fight form capoiera. When they spun on one leg and dove to the floor I recognized the influence of Wells’ body or the Scott Wells that I remember from ten or fifteen years ago. Grubb especially reminded me of Wells’ unique style. The trio section ended with a marvelous thrill of lifts and tumbles, every landing unexpectedly quiet, like cats. Hannon returned, with arms and fingers so alive, her curly mane extending every action of head and spine, and somehow it was her female-ness in response to the trio’s male-ness that filled the space, and took this piece home.

The eight men in the ensemble make a delightful team. In addition to the five men previously mentioned, there is Rajendra Serber, Cason MacBride, and Ryder Darcy. The guys are generous with each other, authentically affectionate, and trustworthy in their attention and precision. Their joy of dancing is infectious and they love to entertain. Wells’ and his dancers are not hesitant to put on a show, to perform tricks, to make us ooh and ahh for a spectacular overhead lift and laugh with an unexpected yet intentional collision. Although they perform some synchronized movement, Wells’ laid-back choreography never enforces conformity. Some dancers shine more than others, but that is more an indicator of accumulated experience than of a lack of necessary talent. A fab flurry of athletic dancing closes the evening. Darcy runs up a wall and flips head over heels. Others run sideways to the wall and propel themselves into dive rolls onto a well-placed mat. Growden is a superb jumper with a loft to rival any high jumper. When he dives horizontally at the brick wall, two other men arrive to pin him, freezing the moment in time. Wells plays often with this kind of sustained time, floating bodies, pausing handstands, and full-body catches that linger, not so much frozen as floating, and then when released the falling weight becomes the momentum that drives the dance onward.

(A few months later I deleted a little joke of a line at the end that seemed to color the previous writing too much. There are comments by two of the men in the cast and another local choreographer - going further with questions of queer, masculinity, dance.)

June 1, 2009

Joah Lowe, my first SF dance teacher

In 2004 David Gere asked me to write a short piece about a dancer who had died of AIDS for his book release celebration. Gere, who came of age as a dance critic at the height of the AIDS epidemic, wrote How To Make Dances in an Epidemic: Tracking Choreography in the Age of AIDS, the first book to examine the interplay of AIDS and choreography in the United States, specifically in relation to gay men. I can't brag too much about the book because I'm lucky to be featured in it, but the writing is lovely and the research is generous and precise.

I decided to write about my first teacher in San Francisco, Joah Lowe. I'm including this 2004 writing about a teacher I worked with in 1982-83 for two reasons. 1) I like the writing. 2) This year when teaching a Queer Performance class at USF I heard from several students that they really weren't aware of how intensely AIDS had impacted gay life and culture. In honor of our ancestors, let's keep remembering.

Letter for Joah Lowe

Dear listener, dear living dancer, dear dead dancer, dear Joah Lowe:

To write a love letter is to willingly open memory’s door. To invite the images and sensations of yesterday to obliterate the distractions of today. But once the door is open everyone comes rushing through. There are so many half-told stories, half-choreographed dances. I’m writing for Joah but I want to write for everyone. For Tracy Rhodes and Peter Kadyk, for Ed Mock and Jim Tyler, for Wayne Corbitt and Arnie Zane, and for all the guys whose names I can’t remember: the one who came to all my sex healing rituals for queer men, the one who gently confronted our Body Electric retreat about our fear of dying, the bedridden one whose voice was barely a whisper yet requested that I come and sing with him at the Hartford St. Zen Hospice.

I’m afraid to write to you. Your presence has become a complicated pattern in a fabric I wear like skin. I hesitate to unravel you individually for fear of my own unraveling. Who am I without you, here, now?

I remember dance class with Joah Lowe, over 20 years ago, in a studio (in this building) at 8th & Folsom. Joah was my first teacher in San Francisco. All the basics that would become Release and Releasing, he shared with us a decade earlier under the names of Aston Patterning, developmental movement, improvisation and whether or not he ever studied with Halprin or Laban, he taught us their rituals as well. Every good dance teacher transcends technique, copywrite, and culture. I’ve been lucky to be in the zone of the one dance, the prayer dance, the now dance, and Joah took me there. He wasn’t the first or the last but because of it he’s unforgettable, indivisible from my story, my dance.

Joah taught a weekly class, an introduction to contemporary dance that involved technique and improvisation. Open to beginners, his class gave me knowledge and confidence to graduate to Lucas Hoving’s Mon-Wed-Fri technique classes, where I folded myself into dance history for the next three years following Lucas from Margie Jenkin’s studio at 15th & Mission, to Footwork (aka Dancers’ Group now Abada Capoeira), the Women’s Building and Third Wave (now Dance Mission). I can’t remember if Joah sent me to Lucas or Lucas sent me to Joah. I’m sure it’s written in some journal that I’ll never read again. I only remember that I refused to study technique with anyone that didn’t also teach improvisation and that’s how I chose them as teachers.

I remember Joah in Lucas’ class and I remember Joah performing but these memories are cloudy, distant. I remember hanging off the ballet bar, learning to maximize the tilt in my pelvis. I remember Joah’s hands on my hips and only later, years later, did I recognize this memory as sexual. Years later when I really learned to fuck, to release into being fucked, I knew what I had learned from Joah. I’ve thought about Joah and those pelvic rolls and tilts a million times, while warming up, studying Pilates or Klein technique, masturbating, fucking, even riding a bike or hanging below freeways, yelling to god (Saliva 88-89, Spell 04)

I remember asking Joah about his own history in dance. All I remember is an injury and some kind of betrayal, I think with Graham technique. I was a wannabe revolutionary pacifist anarchist feminist then and assumed that all orthodoxy caused pain so this out-of-context image became another brick for me to throw at the glass house of Dance. Now I’m one of those who occupy that house, only part-time. I show up to do repairs; to work on additions to the house so more folks can visit. There’s always work to do.

I hope Joah is proud of me. He’s the kind of ancestor from whom I want praise and recognition. I know it’s supposed to go the other way, so I hope that this letter fulfills some of the debt I owe. Joah, thanks a lot. Thanks for welcoming me, for steering me into the future and away from the past. Thanks for paying just enough attention to me, which was not much, because I was not yet ready to be seen, to be revealed, even to myself. Maybe you knew that but probably you just sensed it. You were my first authentically intuitive man. The more I write this the more your body comes to mind, to body. I’m seeing your legs now. They’re very strong. I could go on, but I’m getting nervous, now that your body has caught up to memory and all this presence, yours and mine, is alive, here, now. Thanks again. I bow to you.

With love, Keith

Ps.

Just before printing this letter, I had a twinge of insecurity. Do I really remember? So I googled you. Yes I googled an ancestor. And there you were, noted teacher of Lessons in the Art of Flying, releasing your signature bowling ball to the sky, in a piece called Bowling Lesson #1 – Letting Go of the Ball.

Dance. Lesson. Memory. Body. Letting Go. Love. Thanks.

Photo:

Joah Lowe in his Bowling Lesson #1—Letting Go of the Ball (1984).

Photo by Christine Uomini, courtesy David Gere, lifted from the awesome site The Estate Project. Check it out here:

http://www.artistswithaids.org/index4b.html

May 30, 2009

How To Die, 2006

Homeless USA, 2005

(in French, SDF USA)

Performance: Hennessy & Beckman

Text: Robert Olen Butler & Hennessy

American Tweaker, 2006

Performance: Hennessy, Beckman, Eisen

Text: Kirk Read & Hennessy

Why now?

Rita Felciano, a treasure of Bay Area dance writing, just sent me a review that she wrote in 2006, and coincidentally we are in discussions to restage the work in January 2010, at Dance Mission in San Francisco, as part of A Queer 20th Anniversary, a series events celebrating the 20th-ish anniversary of my first solo performance Saliva. So consider this review and these pics as a promo teaser.

The review:

http://archives.danceviewtimes.com/2006/Autumn/08/sfletter18.html

On my vimeo site you can watch Loren Robertson's 7' promo for How To Die, as well as full versions of both Homeless and Tweaker.

How To Die, 2006, Photos

Top photo:

Top photo:A guy sleeping on the stairs of my house. At the beginning of How to Die I give everyone in the audience a photograph of a homeless or drunk sleeping guy, documented within a block of my place.

Middle photo:

Hennessy in Homeless USA, Photo by Andy Mogg. What you can't see is the 30 foot length of fish line going through the piercing hole in my septum, holding me in place.

Bottom Photo:

Hennessy & Beckman in American Tweaker

Photo by Mark I. Chester. This is the polite photo from the dance of insatiable crystal meth. What you can't see is Eisen, as Sylvester, lipsynching Do Ya Wanna Funk?

Check out Loren Robertson's promo video of How To Die. This link get you to my Vimeo site where both performances (Homeless & Tweaker) are available for online streaming.

Rita Felciano's review of How To Die:

http://archives.danceviewtimes.com/2006/Autumn/08/sfletter18.html

May 24, 2009

Dada Fest, Davis CA

Performer, producer and UC Davis grad student Hope Mirlis organized a sprawling day & night of Dada performances, May 16, 2009, in central Davis.

Riffing off Joseph Beuys explaining his work to a dead rabbit, I whispered, grunted, and ranted for 30 minutes in the 99 F degree heat.

Here are a couple pics snapped by Hilary Bryan and the improv text that I wrote as a kind of rehearsal. Clearly I'm drowning and somehow delighting in the academic texts I'm reading. Fortunately, I finally realized that the critique of spectacle is hideously spectacular.

Help, I just realized that the anti-spectacle is indeed a spectacle

Yes it's true. My DADA needs a MAMA, but not in a heteronormative way, or even in a way that supports the idea of binary gender. My DADA also needs a ZAZA and a MEEMEE, a QUSO and a WEBFART.

What am I trying not to say?

Help, I just realized that the anti-spectacle is indeed a spectacle.

Most specifically I just realized that I am being interpellated by cultural studies texts that challenge the hegemonic culture making machinery. What does that mean? I mean that just when I think I'm resisting, or conspiring an "alternative", I realize that the university, the books produced in academia, and the language that we speak to critique hegemony, spectacle, and ideology are all spectacular distractions shouting, "Hey you, look over here!" Just when we get an embodied awareness of the matrix, we get seduced back into the fold, the plié, the crease, the contraction.

Cultural studies texts induce an internalized and masochistic prison industrial complex, including panopticonic surveillance structures, inescapable tortures, punishments, and incarcerations. The room has no windows. Only a ceiling open to an infinite sun, camera, eye. 24/7 people, I'm talking 24/7.

And I'm an artist. A performance artist past the edge of a nervous break (dance). No one understands me. Which is predetermined. We/they want it that way. And I am only now understanding how deeply embedded this failure is. But embedded does not equal embodied. The msm journalist in Iraq is disembodied, cut off from the socio-political body, in a way that should seem familiar to contemporary artists.

So I'm approaching DADA in Davis with some trepidation, some concern about my nostalgic formulations. Isn't nostalgia a further embedding of the ideology that is cyborg-izing what remains of the living tissue that was my bodymind. Ouch, why doesn't cyborg-izing hurt? Why isn't the surgery of interpellation leaving visible scars at the corporeal points of entry or exchange. And how are these points of contact, penetration, and embeddment, anything but the primary material of my dancing, where dancing is the live moment presence of the dance, the making of the dance, the embodiment of the dance?

So I refuse to dance DADA. I will speak to the dead object that is alive with fetishistic vibrancy. I will share my concerns with whoever can hear me. I know that the ear has not kept up with the eye, i.e., the ear listens from a more archaic paradigm than the eye, cyborgized at a faster rate by visual technologies and the languages that support them. So that means I will also sing, sound, moan, whisper, grate, shift, burp, scratch, vibrate and resonate.

Saturday. Davis. 90 degrees in the shade. I'll see you there wearing shades, dishing shade.

Keith X Hennessy

May 20, 2009

Liz Lerman Dance Exchange, Small Dances About Big Ideas

Photo by

Photo byEnoch Chan

Liz Lerman Dance Exchange

Small Dances About Big Ideas

Kanbar Hall, Jewish Community Center

San Francisco 4/19/2009

Modern dance, beginning with Isadora Duncan’s bare legs, uncorseted breasts and critical rants about women, socialist Russia, dancing children and free bodies, has always been political. Acknowledging the influence of formalism, minimalism, and various styles of abstraction, contemporary dance continues to engage social issues or pose socially resonant questions. But a dance about genocide and international law? Would it be doomed to disappoint or just depress? Despite Liz Lerman’s national reputation, I wasn’t surprised that they were giving tickets away in last minute email blasts to the local dance community. Who wants to see a dance about targeted mass murder? How can a dance meaningfully address horrors of this scale? With four free tickets, I could only convince one friend to accompany me. As I approached the theater I found myself repeating a new motto received from a UC Davis colleague Sampada Aranke, “Failure is generative.” Looking at failed utopian action as ripe with potential shifts the witness/critic role and encourages a more nuanced engagement with a performance or action.

Early in the piece, Lerman sits in a chair, her lap filled with notes, a mic in her hand, and begins to tell a story of being invited to make a dance for a conference at Harvard commemorating the 60th anniversary of the Nuremberg trials. She shared how she expressed doubt in the project, and how she was moved to request personal support and guidance to do the work. Charmed by this meta-performance that welcomed doubt and anticipated failure, I relaxed into my chair.

I have followed Lerman’s career as a choreographer, teacher, and thinker for over 20 years. Her projects inspire and facilitate social dialogue about ethically contentious issues, including refugees, genetic research, and now genocide. The dance company, Liz Lerman Dance Exchange, is diverse with respect to race/ethnicity and age. Lerman says that younger dancers dance better in the presence of older people, and she attributes this to love, the love that older people offer freely to youth. In Small Dances I was more often drawn to the two dancers that I perceived as the eldest, Thomas Dwyer, a tall lean white haired man and Martha Wittman, a long-haired woman who seemed to be the spiritual mother of the piece. Lerman is known in classrooms and studios around the world for Liz Lerman’s Critical Response, a methodology, which guides artists and teachers to give critical feedback without assuming culturally specific standards. The artist-centered process is based more in questioning than judging; it challenges the ideas of a common standard of artistic quality or aesthetic sense and supports cross-cultural collaboration. This multi-decade dedication to the art of social justice makes Lerman a likely candidate from whom to request a dance about the failure of international law to prevent genocide. Small Dances About Big Ideas premiered in November, 2005, at "Pursuing Human Dignity: The Legacies of Nuremberg for International Law, Human Rights and Education.”

In her opening monologue Lerman advocates a role for the body in political and historical discourse, especially in response to the often paralyzing impact of information and opinion. So what do the bodies do in this dance? Dramatic expression. Mimetic gesture. Representational images. The dancers line-up and get shot with staccato staggering and dense falls to the ground. They run in fear. Matt Mahaney represents Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term genocide and successfully advocated for a special class of international laws. The dynamic Mahaney/Lemkin jumps and waves, trying to get attention for his cause. When he fails, he falls repeatedly, almost violently. Stylistically the dancing and gestures recall socialist-inspired expressionist dance from the 30s, or the 70s ground-breaking feminist collective The Wallflower Order (which became SF’s Dance Brigade.) Ted Johnson, who plays the judge, could have done the same postures in Kurt Joos’ famed anti-war dance The Green Table (1932). Small Dances is postmodern in form but not in gesture, except when they fall, and here they release into the floor, spiraling to soften the impact. A younger man, Benjamin Wegman, shares the narrator role with Lerman. He introduces the characters represented by the dancers. There are the three mythical Norns (Shula Strassfeld, Meghan Bowden, and Wittman), Norse deities older than god, akin to Fates, who inhabited the waters in and under Nuremberg. Their natural hair, tattered scarves, long dresses, and a concern for the others, attempted to conjure a mythical feminine presence. There is Lemkin and the stoic, shiny bald, black robed Judge. Cassie Meador played The Bone Woman, based on forensic anthropologist Clea Koff who investigated atrocities in Rwanda. And there were two other characters that I called the man from Rwanda (Fiifi Abadoo) and the Bosnian woman (Sarah Levitt). I wanted more contact with these dancers, wanted to know which language they were actually speaking (as opposed to the languages I assumed for them), wanted to know even a hint of their personal story. How do they function, or identify themselves within the American-ness of Lerman’s perspective? Were they born here or there or where? The narrator played a reporter, a watcher. He seemed to speak both for Lerman and for us. What does genocide look like from across the gap of geography or generation? What does the witness do with the harrowing information and the implication of responsibility? The question was put before us, within us, and this alone validated the performance.

Lerman and her dancers wandered through the material like devastated archeologists, stepping over bodies, pausing to investigate the bones which hold all the memory of violence, daring to record the details of machete and sex. They touched bodies as if listening to their past. “Rape cannot be claimed as self-defense, ” someone claims. We have to think about that. Now. Lerman’s choreographic process led us on a difficult descent. She told us of being haunted by stories and bodies, but unable to stop the research. There’s too much to read. She lost the ability to remember in the evening a simple fact that she was told in the morning. And then she can’t sleep.

The most successful moment in the work led to its paradoxical disappointment. With all eyes looking forward to the proscenium stage, we were jolted by a loud sound at the back of the house. We turned to see the source of disruption, the narrator. He shook the protective aisle rail like it was a cage. Something fell and broke. It seemed dangerous, like maybe he had snapped, and had pushed the ‘play’ too far. The room was still, tense, charged. He told us that he was done listening, that he didn’t want to hear anymore. He questioned what was happening, and therefore he questioned our role, like his, of watching. He said, it’s good to talk about genocide, even to just try out the word, and that maybe we should just talk amongst ourselves. He was walking towards the stage as he spoke and we could now see that the other performers were watching him. No one was dancing. The stage was quiet. Lerman sat in the shadows, attentive. The house lights were up and we started to talk. I was with Neil MacLean, a researcher who has spent years on the questions posed by this project. I spoke about my resistance to the dancing and representational movement. I told him that the gesture of one arm chopping the other arm was done by David Byrne in the early 80s Stop Making Sense tour and I’ve thought it weird and undecipherable in too many choreographies since then. Neil sharped the focus and told me why he and many others find the term genocide problematic. He said that it should be ethnocide or something to indicate that it is not people (genus) but a specific family of people (ethnicity) that is under attack. We discussed how the politics of identity, including politics of naming and resisting genocide, often subvert potential solidarity by intensifying cultural and ethnic difference. And then our attention was guided back to the stage, and we were led in a group dance of mimetic gestures about pulling a story from the space around us, holding it, and then passing it to the person beside us. Although 90% of the audience participated in this follow-the-leader dance, I found it difficult to participate whole heartedly. It seemed to suggest a common experience and way of processing the intensity of the material, but really it served to pull us out of the intensity and back to dancing, as if synchronized dancing is a unifying experience, when Lerman and I both know that stories, bodies, and gestures are loaded with positions and identities that are more exclusive than inclusive.

The work continued for another 15 minutes or so, but I was still stuck in the break, in the disruption, in the moment of questioning what we were doing in a theater with this handsome group of sincere and talented people, and what good might come from speaking the word genocide aloud, together. Two weeks later, I’m still bothered, still asking.

I heard that after the performance, a World War II vet asked Lerman,“Is this adequate?” She acknowledged that it wasn’t. Of course the work failed to save lives already gone or rewrite UN charters or prosecute countries, including the US, who regularly shit on international law. I gathered with friends in the lobby. We were the minority who didn’t stay for the post-show discussion with Lerman & company. The lobby chat was lively and sharp. Although we had perspectives that resonated, no two of us had the same opinions about the work, about what happened, about what didn’t, what should have or might have. Respect for the work was our most shared experience. We were inspired to challenge or defend art’s role in addressing state violence. We felt pressed to reconsider historic atrocities and to strategize ways to prevent and recover from the kind of totalizing violence which permanently scars time, space, and community. This small dance, only 60 minutes long, idiosyncratic and maybe even trite, invited us to interact with history, with how violence, rape, and massacre are remembered and historicized. Lerman and company not only dared to accept this ethical imperative, but they held our hand and invited us to dance along, among the bones, which continue to haunt and to speak. Honoring a lineage of politically engaged choreographies, Liz Lerman’s Small Dances About Big Ideas touches people and helps us to listen.

May 19, 2009

Big Art Group's S.O.S. at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts

Big Art Group encouraged the audience to use their cellphones to take pics of the performance. These were snapped by Ernie Lafky who was sitting behind me. The top photo captures the balloon-gasm which concluded the performance.

BIG ART GROUP

S.O.S.

Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco

April 23-25, 2009, 8pm

Q: “We’re parodies, what more can we do?”

A: “You’re a fool, dear.”

Big Art Group’s S.O.S. is (theater of the) Ridiculous B movie camp that may or may not be something else entirely. The hyper talented cast plays a trashy queer family of post drag revolutionaries sucking into the big nothing that might or might not be Realness, I mean, Realness ®. The gifted text crams the jargon of all the new academic Studies (Cultural, Gender, Performance, Queer, American) into chaotic fusion with the equally disturbing textual simulacra (infinite copies of ideological cliché) of the non-profit industrial complex. Are you with me? Neither am I. Now add lots of costumes, wigs, lights, loud music, body mics, live and prerecorded video projections, and children’s theater puppet crafts. (I mean by children not for children.)

S.O.S. is created by Caden Manson (director as well as video, set & costume designer), Jemma Nelson (writer, dramaturg, sound design) and Big Art Group. The script is near genius. I was jealous that I didn't write it first. The performers detailed professionalism does not detract from their freakish dissonance with professional theater. These people shriek and moan. I heart these fierce queens. The performance devolves more like a crisis, a situation. Picture a spectacular collision of lowbrow and high-tech with the budget and attitude of Vienna’s Superamas or Meg Stuart at Berlin’s Volksbuhne or an early opera by Peter Sellers. Big. Messy. Witty.

Eight large screens. Too many cameras to count. (They call it Real-Time Film.) More cheap f/x than you can shake an ur-text at. The fake fights of Reality TV. Facebook gossip. Twitters in a Cockettes film of Patricia Nixon’s wedding. And the Blaire Witch Project except that instead of dumbass actors who talk like mall rats lost in a suburban forest, it’s animals (or theme park mascots who think they’re animals) lost in a forest of technology. Anyway they’ve escaped the cage, their libido is wack, and they have no vocabulary to articulate their crisis.

Low-tech flashlights meet high-tech body harness video cams that televise the performer’s facial minutia in a banal mimicry of TV ads and drugged youtube videos. I say Hegemony, you say Fabulous. Hegemony! Fabulous!

These virtuosic speed talkers spit postdramatic text mashups of infomercial, black drag queens, academic critiques of accumulation and identity politics, spasms of relentless self-obsession and pop nostalgia for Patty Hearst era revolutionaries. Yes, its’ the Realness Liberation Front. Cut to Realness ® logo. Cut back to actor, queen, slave. Cut to stage hand (queen, slave) jiggling photo for earthquake-like background. Cut back to actor, fauxqueen, slave, spewing verbiage that we know too well.

Most of you won’t know what I mean when I say it reminded me of a particularly wild night at Trannyshack with a super fat budget but of course SF anarcho-queens would never agree to this many rehearsals and would never be granted the $50,000 in video equipment. Or was it more?

Frustrated screams morph into orgasmic moans and then neurotic giggles. “That is so totally fucked up.” I agree. “You are preparing us for consumption, for transition.” Wait I get the consumption bit but what do you mean by transition? Too late, they’ve spun faster than minds can acquire, “Slipstreaming past each other’s essentiality.” I’ll say. “The philosophy of the hopeless will be done with. We will begin the eon of a new Nothing!” These people look like they’re on acid but they talk like they’re on crystal.

Insane costumes of hundreds of those long twisted clown balloons consume the actor within. S.O.S.’s increasingly mad antics climax with an orgy of balloon attack and mic feedback. My buddy Jeff Mooney points out that this is the only time they directly touched each other. Meanwhile the escalation of spectacular nothingness continues to explode outwards while simultaneously sucking everything into its black holes of non-center. Lights out. The end. The revolution will be ridiculous.

What happened? Big Art Group re-presents trashy 70's drag freaks with massive techno budgets and very ambitious updates of Ludlum and Cockette. The text was pretty brilliant and the performers are delish but is it good or bad or just something? After they sucked us all into the big Nothing, most of us left empty, as in, I feel empty. Is Big Art Group the Dada provocateurs of our time: meaningless art to confront meaningless spasms and twitters of unending war and capital accumulation? Why don't I love it the way I love the Dada of 1916? Half my friends thought that S.O.S. constructed a brilliant and empty spectacle about the brilliance and emptiness of the capitalist spectacle. How brilliant! How empty! The rest acted like they’d snorted poppers and ran naked into a summer rain, smiling widely.

Then I realized that as much as it had one foot in the 70s and another in the 00s (pronounced, the naughts), Big Art Group’s S.O.S had another ancestor in The Living Theatre’s 1963 production of The Brig. The play, written by Kenneth H. Brown, is a hyperrealist representation of a US Marine prison in 1950s Korea. In this hellish dystopia the men can’t speak to each other. The stage is a complex grid of territories and every line crossed requires a ritual of submission and humiliation. The audience knows it’s bad, it’s hell, and they might be there forever. In S.O.S. we don’t even know. We think it’s fun or smartly ironic. The animals think they’ve escaped the enclosure but of course they can’t survive in the wild. They can’t even tell that there is no wild, that there’s only enclosure, surveillance, projection, a reality game. Their solidarity breaks down and they consume each other. In The Brig someone tries to escape. He cries out, “I am not a number. I have a name!” He is beaten and carried away in a strait jacket. In S.O.S, no one tries to escape. There’s nowhere to go. It’s all a borderland swamp where escape and captivity merge. Submission and humiliation are natural traits, embodied. We think we chose these products, these rules, these enclosures. Hyper connectivity and abbreviated codes for accelerated chat echo in the prison of a technosphere maintained by a panopticon of personalized webcams. We’re all on TV all the time. Ok children, everybody surveil themselves, turn yourselves in, beat yourself up. In both projects – The Brig and S.O.S. - the performers sacrifice themselves to an equally rigorous labor of seemingly meaningless gestures – stand here, cross this line, don’t move, move like this – all the better to control their every desire. The demand on the actors, by the director and the writer, reproduces a totalitarian regime rooted in some kind of consensual SM that any ballet dancer or football player would recognize. A ritual of sacrifice enacted on the young bodies of the players.

According to Big Art Group’s website, this sacrificial ritual called S.O.S. has a much older ancestor than The Living Theater. In 1913, Le Sacre du Printemps caused some kind of riot or disruption with Stravinsky’s dissonant and polyrhythmic score and Nijinsky’s choreography for a pagan girl, sacrificed by her own people. She dances herself to death. Attempting a “celebration of renewal through chaos” S.O.S. revisits the scene of the (art) crime to ask the question, "Can sacrifice create a new beginning?"

May 18, 2009

Lizz Roman & Dancers AT PLAY

Photo of Sonya Smith on the Dance Mission fire escape by Rapt Productions.

Photo of Sonya Smith on the Dance Mission fire escape by Rapt Productions.At Play

Lizz Roman & Dancers

Friday, May 15, 2009

Dance Mission Theater, San Francisco

I hate missing anything. I’m very good at negotiating site-specific performance and pride myself in being a good ‘participant’. In At Play, Lizz Roman’s newest choreography of architectural archeology, a vibrant quintet of dancers enlivens the walls, windows, doorframes, studios, hallways, bathrooms, and fire escapes of Dance Mission Theater. And it’s impossible to see everything. Shit. Then I realized that partial viewing is the point. It’s about the unseen, the surprise, the revelation and the sudden disappearance. It’s about the periphery in relation to the center and it’s about, “Where did she go?” and “Where did he come from?” Not only can the whole choreography not be seen, Roman challenges the idea that there is a whole.

Just as someone disappears from view you discover that someone else has been dancing for five minutes without you having noticed. Roman plays with our attention, abruptly tricks us, and then gently leads us. With the audience crowded into spaces never intended for public gathering, it’s clear that we’re not all watching the same thing. We can’t. Forced to choose, we follow different impulses and while half the audience has their necks craned to the right, the others are leaning to the left to see who just emerged from the stairwell.

A basic element of Roman’s site-specific dances, like most site or environmental performance, is to reveal the unnoticed and to bring our visual attention to places we might usually ignore. That’s why I refer to it as architectural archeology. However, Roman and her dancers seem as concerned with imaginal and archetypal spaces as with the visual or actual site. Watching a dancer fall out of our line of sight we might ask, “Who caught that woman as she fell into another room? What’s around that corner?”

I catch myself wondering if people dance in and out of bathrooms in other cities as much as they do in San Francisco*. Then I wonder how many people will find a new way to perform the fire escapes and external brick wall of Dance Mission. The Dance Brigade, Project Bandaloop, Jo Kreiter/Flyaway and I have all done it. This is neither the natural outdoor performance of Isadora nor Ted Shawn’s naked men at Jacob’s Pillow. This is closer to Trisha Brown’s 1970s experiments with rigged dancers walking down the sides of buildings, but subtract the minimalism, or Anna Halprin’s dancers on scaffolds in the 60s, but add a released and lyrical dance vocabulary that was not yet imaginable 30 or 40 years ago.

Co-composers Alex Kelly on cello and electronics and Clyde Sheets on percussion and electronics, parallel the experiments of the dancers. When some sounds, textures, or rhythms are prominent, an undercurrent of other sounds is happening in the sonic periphery. A child’s voice (Dahlia, Kelly’s daughter) recites her A, B, C’s as if she’s in the next room or just happened to sit next to daddy while the composers recorded a driving beat. Although we often can’t see the musicians except when traveling from one site to the next, we know they’re playing live. For the outdoor section, they play like neo-gypsy street musicians, using battery powered amps, a snare, Kelly’s electro cello, and a CD of prerecorded samples that was too mute to recall. Again, an evocative partiality occurs. Someone closer to that amp will remember it differently. Others might not have heard them singing live, unmic’d, briefly.

At every performance choreographed by Lizz Roman, I’m impressed with the ensemble, the team, the family of dancers. They shine as individuals, seem truly affectionate in duets, and are solid as an ensemble. They seem somehow unlikely as a team. When I heard that ODC veteran Brian Fisher (most recently seen dancing with Sean Dorsey) was in Lizz’s current company, I was surprised. But Fisher, again and again, shows us what a generous, willing, and versatile dancer he can be. Afterwards I told him that I’d never seen him do so many hand balances. He responded that he’d actually been a gymnast before a dancer. Roman treats the group democratically, sharing solos, alternating duets. Sure the men lift the women higher and more often, but women also support the men, and the same-sex lifting is where the affection is visceral. (But I’m biased towards actions that read as queer and feminist.) The way these dancers move between solo, duet, and company, alternating central focus and periphery, reveals a group bond that is more than a willful accumulation of disciplined labor. Maybe this invisible yet tangible bond is part of the unseen - the vibrant imaginary - that the work evokes.